The World was her Stage in the 20th Century

THE FORMATIVE YEARS: Getting on Stage

"There was a lot of hard work, glamour, and a good deal of unpremeditated comedy. There was also some heartbreak.. but by and large, life has been very good to me." -- La Meri in her autobiography, Dance out the Answer.La Meri was born in Louisville, Kentucky in May of 1898 and christened Russell Meriwether Hughes (after her father, oddly enough). She described her father as joyfully hardworking and her mother as a woman of great beauty and Scottish stubbornness... all of which were inherited by their daughter. Her family moved frequently while her father built up his successful business enterprises, eventually settling in San Antonio, Texas, which at the time had one paved street. Her family sent her back to Louisville for boarding school until she was of high school age, at which point the whole family established their permanent residence in San Antonio.

Theatre and dance were important aspects of her childhood life; world-famous dance artists and companies toured everywhere, and La Meri saw a good deal more great dance in her little corner of the world than many modern girls do. Performances by Anna Pavlova, La Argentina, and the Ballet Russes inspired music and ballet and Spanish dance lessons at the local conservatories. A performance by the Denishawn Company inspired an interest in 'Oriental' dancing.

We wore Oriental costumes and, as could be predicted, I conducted classes in Oriental dancing. In my abysmal ignorance Oriental was all of a piece, the Orient being a big romantic domain of harems, flying carpets, and yogis; and I casually mixed Moorish, Indian, Turkish, Armenian and what-have-you to suit the requirements of the moment.

La Meri's appearances at local recitals and fetes gave her early insight into her personal IT quality on stage.

There are, I learned, ways of carrying off inexpert dancing. Many attributes not acquired in the classroom will hold an audience. They have to do with character and personality in the dancer and stem from an individual and great love for the theatre. A feeling of being personally at home on the stage can cause the very curtains to come to life. Then there is that sub-conscious bond of unity with an audience that can translate a performance into a lover's dialogue, exchanged by two lovers finding themselves miraculously alone together in time and space.

Her father died when she was sixteen, but his investments provided his family with financial security. Her mother was able to manage her grief and assist her daughters with their career interests, but La Meri described her as never the same again.

In 1916 La Meri enrolled at a College of Industrial Arts in Texas. Her autobiography provides no details of her official college curriculum. It does, however, describe writing verses, planning a literary career, starting the school's recreational Dance program, playing in the orchestra and performing in school plays.

How La Meri managed to convince her mother that an artistic career was a viable career for a woman is not spelled out anywhere, but for the WWI era it was an unusual choice. It might have been the many incremental local successes which made the larger stages seem reasonable.

In 1920, after La Meri succeeded in publishing several poems, her mother agreed to take her to New York to try her luck at a literary career. When she was unable to sell her work, they returned to San Antonio. She then took up performing, playing violin and singing at local events; and then won a beauty contest and a role in a small movie company production. Her local dancing engagements became increasingly numerous with the War Department entertainment units and the American Legion. She then became a frequent performer at a local theatre, providing dancing and singing entertainment as the opening act for the featured silent film. When the theatre's orchestra conductor booked a run at a cinema palace in New Orleans, La Meri and her mother packed their suitcases for a couple of weeks there. Then he booked the act into Atlanta, and another town, and another. Several months later, La Meri and her mother found themselves in New York City, at which point La Meri decided on a career in the theatre. With family nearby at West Point to provide a home-away-from-home on the weekends, La Meri's mother agreed to an allowance of $20 a week and went back to San Antonio.

The career in theatre did not materialize. When her morale began to slide, her mother returned to New York and they settled down in a theatrical hotel just off Broadway. La Meri's break came when she was hired to play castanets for a Spanish dancer in a vaudeville act, a skill she had acquired when she studied Spanish dance in San Antonio. During the course of the job, she became friends with a dancer who got her into Maria Montero's troupe, at that time the finest Spanish dancer in America. Here La Meri obtained the touring experience she needed to get hired at other venues, which in turn led to an interview with the impresario Guido Carreras, an Italian baron who had managed both dancers Nijinsky and Pavlova. She described Mr. Carreras's efforts to evaluate her artistic talents with a sense of humor.

The immortal Duse had died in his arms in a Pittsburgh hotel. Since he had listened constantly to her glorious voice, my small abilities as an actress were waved aside... [He] had me play for a gifted violinist. The verdict was clear and to the point: "If she had a decent bow... and a good violin and worked hard for not less than eight years, I think she might be, well, all right."

I sang for another friend of Carreras's, a singing coach of standing. When I concluded...this gentleman, a Hungarian of gaiety he was, said to me affably, "you have a great deal of artistic understanding... and, so far as I can discover, no voice at all."

[Carreras] called still another friend. Amalia Molina, the Queen of the Castanets, came to see me dance. I did the jota..."of course, her castanets..." Madame dismissed my castanets with an impressive wave of the hand. "But, " she went on, "yes...yes, I have to say she has something. ... But what is it?"

At this point, Carreras and La Meri decided that she would throw her lot in with dance, and that Carreras would manage her. Her first engagement was at a theatre in Mexico City, Mexico. That concert La Meri also described with humor:

The orchestra struck up my music; I was introduced; I ran out on to the glassy floor... and slipped. Both feet flew into the air. I sat down with a spine-shaking jolt. My tall comb was knocked askew; one castanet shell broke; the heel flew off one shoe.... what would you have done?... I sat there. For about fifteen seconds all of us, audience and I, laughed uproariously. I then picked myself up and limped off...changed shoes and castanets...I got through the performance with no further mishap. As a first appearance in a very dance-conscious capital it was baroque, but it had one effect not achieved by all first performances -- it made us all friends.

Her debut was a complete success, and Carreras was able to book three months of engagements at Mexico City venues. And it was here that La Meri acquired her permanent stage name. One of her interviewers decided to shorten her stage name, Meri Hughes, to a form more compatible with the Spanish tongue, and proceeded to write about her as La Meri. La Meri she remained throughout her entire career.

THE TOURING YEARS

Guido Carreras and La Meri quickly, if not immediately, became romantically involved. "Mother liked Carreras personally very much. But she found ways to remind me that he was 20 years my senior; his background could hardly have been more different from my own. Nevertheless she recognized that, here at last, somebody was successfully channelling my createive talents into constructive concrete expression." Carreras was indeed an ideal manager for La Meri in many ways. He had a lifetime of experience managing world-wide tours for important artists; he knew the venues, he knew the conditions, and he knew how to persuade and bribe when necessary. He defended her from over-zealous admirers, and solved logistics problems when she was ill. The young La Meri worshipped him, which, unfortunately, meant she also imbibed his opinion that her ethnic dancing was a secondary art form. When she began to grown into her own person she found herself bitterly resenting this.Guido Carreras helped her assemble a company which then toured Mexico, Cuba, South America, Europe, America, Australia, Tasmania, India, Burma, Java, Singapore, the Philippines, Shanghai, and Japan. Since it was common for companies on tour to stay in one city for several days or weeks at a time, La Meri took the opportunity to study during the day with the best local teachers she could find while performing at night. After several tours of performing at night and studying all day, her dance genius and hard work resulted in an amazing repertoire of ethnic dances, mastered well enough to earn the approval of experts. Her expertise in Spanish and Indian dancing became legendary.

In Granada, she studied authentic gypsy dance from one of the best dancers and had a young bullfighter dedicate a bull to her. In Sevilla she took private lessons with Otero and had her tailed dress made by a famous dressmaker. She made a splash in Viena and in Berlin, where she was introduced to Anna Pavlova, who requested that she give a candid opinion of Pavlova's Mexican dance. "I don't remember now exactly what I said to her. I remember only that I discovered I could discuss dancing objectively and intelligently, and that I felt, perhaps for the first time, that I had ideas on the subject which were definate and my own."

In Morocco she studied the danse du ventre with the Sultan's favorite dancer. "When I studied in Fez in 1929, I was told by my teacher, Fatma, that the danse du ventre was of ritualistic origin and was, at that time, still performed at the bedsides of women in childbirth... Among the so-called primitive peoples there are many examples of therapy dances which involve the pelvis and abdomen. Modern Hawaii has forgotten her 'ohelo' hula, a dance done in a reclining position for pregnancy therapy. In 1936 the Maoris of New Zealand still performed their version of this dance, or, at least, the older people did. At that time it brought forth only laughter from watching Maoris, but in ancient times it was done by all, every morning, as a therapeutic exercise. So I find reason enough to be convinced that the danse du ventre had its origins in ritual, and not in the sexual excitation which is too often attributed to it...

"As in all forms of dance, there are mediocre as well as good exponents. One can scarcely hope to see the best in the tourist-traps of the ports, yet many thoughtless travelers will form an outspoken opinon of the entire dance-form from spending one evening in a Tunis cafe. Also, much of the over-all emotional impact is lost on the average Westerner since he has no audial sympathy with the accompanying music. To the Asian, the music plays no small part in the evocation of the dance-mood."

Describing her training with Fatma: "There is a small orchestra that follows the dancer-teacher, who goes through the dance while the pupil follows along as best she can. This is repeated until the dance is learned. It is a slow, painful method, beset with surprisesfor the green Westerner... as a footnote to the system of on-the-spot improvisation, let me tell you of my experience with a Moroccan orchestra. During the Paris Exposition in 1930 I gave a concert at the Champs-Elyees Theatre in which I used, for my ethnic dance section, typical orchestras from several countries which were represented at the Exposition. To my requests for a rehearsal, each of these yielded, save only the Moroccans. On the night of the performance they arrived, asked me what dance I was doing, followed me onto the stage, and played until I made my exit. For a Westerner, it was not a relaxing experience!"

In Paris she saw Uday Shankar and his company perform. "[Giving] me my first sight of East Indian dancing. I could not know how much it would mean to my future, but I went away from that performance walking on air. What an excitingly beautiful art! What a matchless artist to communicate it! I took courage in my hands and introduced myself to this God-like dancer." Mr Shankar, when entreated for lessons, responded that he did not teach, but he allowed her to attend his company rehearsals, gave her books and records to study and who helped her create an Indian dance that remained in her repetoire for years. This encounter with Uday was catalytic, although it would be several years before she would go to India.

In June, 1931, La Meri and Carreras married in London. "After four years of anxiously awaiting this outcome I found, to my horror, that I felt qualms. I had nightmares and adrupt crying spells and the near-panic of claustrophobia. Perhaps, I told myself, it was only a birde's usual jitters. Or perhaps, I tried not to tell myself, it was a deep, inner conflict between my bedrock layer of old-fashioned propriety and my new-burgeoning strength as an artist."

The newly-weds went straight from London to a Tuscan village in Italy. Carreras, twenty years older, wanted to settle down and retire. La Meri, 33, was coming into her full artistic strength. Carreras got her a job at the R.Academia dei Fidenti, where she held classes, arranged concerts, and took time to write her book, Dance as an Art-Form.

Her move back into the world of the touring artist was facilitated by an invitation from the Vienna Dance Congress to represent Italy. "It was my all-ethnic performance and I was received with a warmth I was never to forget - how an artiste feels, with a quivering antenna of the heart, the waves which sweep across the footlights from the audience." After repeated encores, she said, in German, "The programme is fast and I am tired, but I love you," which further endeared her to the audience. London was next, which started out with a cool welcome but ended up to be a great success. Then, Mr Longden, an Australian impressario, proposed that she tour the Orient.

INDIA!

Usha Venkateswaram, in her Preface to the Life and Times of La Meri, describes the impact that Western dance artists had on the revival of Indian dance:The period between 1920 and 1940 was rich with cultural awakening and interaction in the field of dance... There was a spurt of interest in the dances of the Orient and all the creative dancers in the West adapted various aspects from this rich heritage which suited their taste and aptitude. Those who came to India went back with their own impressions of the dance forms. Some called it the 'Hindu dance' and others 'Nautch.' India, under British colonial rule, was prevented from freely practising her traditional art forms, especially the temple dances, performed by the devadasis as an offering to God... Fortunately, this art was kept alive by the dedicated and diligent Nattuvanars, the hereditary teachers of traditional dance, and by the devadasis within their family circles.

It was during this period that Anna Pavlova, Ruth St Denis and La Meri visited India. Pavlova was greatly impressed by the spiritual quality of these dances and introduced them in her ballet. She also invited Uday Shankar to dance with her and be a part of her troupe. It was Uday Shankar who helped her to understand and present the Indian dance.

Ruth St. Denis visited India in 1926 with Ted Shawn and she succeeded in capturing some of the impressions and essence of the country, which she interpreted in her own way.

Then years after Ruth St Denis, La Meri burst upon the scene with her visit to India... She was fortunate to see Bhanumathi and Varalakshmi perform Bharatanatyam at the very beginning of her stay. She was able to peruade their dance teacher, Guru Vidivelu Pillai, to teach her this dificult art form... she was able to give a performance in Madras, along with Bhanumathi and Varalakshmi within three months. Thereafter she studied Kathak under Ram Dutt Misra in Lucknow and recorded the music for the dances in Calcutta to take back with her.

In May of 1936, La Meri embarked for Australia to begin her tour. She was met with great enthusiasm, and many more performances were scheduled, with her performing sixty different dances during her engagement. 108 concerts total in five months! As usual, she spent all spare moments learning local dances. But it was in Madras that she met with the most appreciation for the repetoire that she already had and where the seed planted by her encounter with Uday Shankar took root and blossomed. Mr Seshagiri, the director of the local Indian Renaissance Theatre, invited her to a recital by the two foremost Bharatanatyam dancers, Varalakshmi and Bhanumathi, and then persuaded their teacher, Guru Papanasam Vadivelu Pillai, to take her on as a student. "Guru Vadivelu in the beginning was skeptical and somewhat sarcatic. However, he too learned something during that same first lesson, namely that I had the capacity to work for hours at a stretch without resting and, whereas his other pupils would burst into tears and rush from the room, that I could take any amount of correction."

At the end of the eighth lesson Vadivelu remarked that with three months of training he would make her the best dancer in India, a promise which he fulfilled. After a brief trip to Bangalore, she returned and added lessons in abhinaya with Srimati Gauri Ammal to her lessons with Vadivelu. Before she left India, she performed one solo in a concert by Varalakshmi and Bhanumathi which made her the toast of Madras.

Kapila Vatsyayan, in her Foreword to the Life and Times of La Meri: "The story of Ruth St Denis is well-known and her response to Indian dance well documented, but La Meri, the younger, no less adventurous and yet more painstaking and serious, was indeed the first to lay the foundations of the first serious school of a systemized training of Indian dance, specially Bharatanatyam. No longer was it an impressionistic reconstruction of a mysterious Orient through a kinetic vocabulary totally alien to the East. Instead, it was a purposive and painstaking attempt to understand and analyze another vocabulary of body language and kinesthetics. She succeeded admirably." La Meri herself wrote: "I know that it was in India I reached a pont at which my work became predominantly important to me, a point at which I began to feel that I was important to my work. I began to find new strength within myself, fresh faith in my own capabilities. The little puppet Trilby began to dissolve."

It was in Bangalore that La Meri and a young Ram Gopal were introduced to each other by the owner of the Opera House in which she was performing. La Meri thought him a very promising dancer and he was very anxious to join their company. Ram Gopal quickly became her dance partner and instructor as well as soloist and apprentice in stagecraft.

In Calcutta she engaged an Indian orchestra to record music for her dances. In Lucknow she studied Kathak with Sri Ram Dutt Misra, finding that her skill with Spanish flamenco was of great aid since Kathak "is based largely on rhythmic floor contacts." Her last concert in India was at Delhi, after which they travelled to Rangoon, Burma, where she studied Pwe with the legendary U.P.O Sein, who, after seeing her perform in her first concert, commanded her to come to his house the next morning and learn Burmese dances. He put her on a schedule of 4 hours of instruction per day, but his follow-the-bouncing-butt style of teaching frustrated her. "[Never] did he do the dance twice in the same way, never did he finish with the record; never did I find out what rhythm he kept, if any. So much work to so little purpose." However, he insisted that she perform Pwe at her second concert and the public and critics declared themselves well pleased.

La Meri and company then travelled to Singapore and to Java. She spent the days on the boat journey to Java rehearsing and taking lessons with Ram Gopal. In the Phillipines Ram Gopal and Rajoo, their tabla player, were arrested and the company costumes and props seized on a paperwork technicality. Bribes were necessary to release both people and goods. Despite the uproar, La Meri continued her standard regimen of dance lessons with local teachers.

Hong Kong was next and they were well received, but all was not well in the world outside. The Japanese were beginning their program of expansion: Indochina, the Philippines, Thailand, Shanghai. Just before the invasion of Burma and Hong Kong, La Meri and company moved on to Tokyo, where they spent three months reheasing, overhauling their costumes, and attending theatre shows. La Meri took lessons in Japanese dancing from the best teacher she could find and gave an lecture on the Indian origins of Japanese dance which was well received. However, the war caught up with them, and they headed back to the United States via Hawaii, where La Meri spent time studying Hula.

Exactly what happened between Ram Gopal, La Meri and Guido Carreras at the point of their departure from Japan remains a mystery. Mr Longden returned to Europe, Rajoo returned to India, but Ram Gopal remained in Japan. The company was undoubtably in a hurry, perhaps even frantic. Ram Gopal's goal when joining the company was to return to India a successful artist. The arrival in Japan had previously been agreed upon as the point at which Gopal would start drawing a salary: perhaps he wanted more money than they were able or willing to pay. Perhaps it was obvious that the War was going to greatly restrict their ability to support themselves with dance tours. Gopal claimed that La Meri decided to part ways with him after a Tokyo concert in which his dancing drew reviews that outshone hers. He omitted mentioning that the concert was not well attended and that the Japanese tour was abruptly terminated when war broke out. La Meri wrote that she and Guido decided to return to America and Gopal decided to stay. Gopal described himself as abandoned, standing on a street corner with two boxes of costumes and a suit, heartbroken, and waiting for friends to rescue his "starving, penniless, hungry and cold" self, despite the fact that he seems have spent only a few hours in a park waiting for a ride to the house of a new patron.

Ram Gopal, writing about La Meri in 1957, described his apprenticeship with La Meri with bitterness and a few phrases of faint damning praise.

During her Season at the Opera House in Bangalore I taught her all she ever knew of Kathakali, as she had never been to Malabar, did not intend to go there, and perferred to learn, anyway, from me directly. Finally it was decided that after her enthusiastic talk of her forth-coming Far East tour, my parents agreed that I could join her...Perched up high on her loaded lorry full of costume trunks, to and from boats and stations, sweeping the stage, and helping to clean, put up and remove her black velvet tabs, these and lots of other jobs were mine during that period of apprenticeship. We visited all the big cities in India and then from Calcutta went on to Rangoon, Malaya, Java, the Phillipines, China and finally Japan. Everywhere I was studying the dances which this dancer attempted to learn... In my opinion she completely ignored the spiritual and mental attitude and consequently her interpretations were more mental than 'under the skin ' studies, authentic as they were.

It was an exciting lesson to watch La Meri put on her makeup, or should I say change her face with the flick of an eyebrow pencil and lipstick to suit the numerous characters she attempted to portray. I thought how intelligently and swiftly she changed! She was a Hula dancer one moment, then Spanish the next, and as quickly changed to Russian ballet technique. Now she appeared as a Mexican doing the Jarabe Tapatio, dancing on the brim of her hat, then she was a Nijinski faun, a Marwari Nautch woman, a Burmese belle, a Javanes princess, the Spirit of a lake, a mechanical straw doll, mechanical lifeless, still. I am only mentioning a few of her numbers... I began to think as time went on, as we moved from country to country, that there was something very entertaining and clever about what she did, and she did it with every ounce of conviction and sincerity of which she was capable. But I felt that if it took Pavlova a lifetime to perfect one technique alone, as it did with Nijinski and Karsavina, and my great masters in India, how could any one dancer attempt to present an Evening of the World's Dances?

Nevertheless, the first-hand experiences I had of watching, learning, working and suffering the most abominable discomforts compared to home all prepared me for the future. So many Indian dancers... imagine that fame, success and money pour in at the box office... Many Indian dancers suffer under this misaprehension and the few who have tried have had disasterous results, unless like Uday Shankar they started learning from the beginning with humility and hard work.

La Meri never gave any public details about her problems with Ram Gopal, but in her diary she penned a few:

- I surely will not be associated with Ram on any project short of a Broadway production where I handle only American kids.

- The insincerity of Ram is appalling! He feels that only money is the answer to all the problems, and his childish lies and subterfuge are pathetic (when they are not irritating).

Despite Ram Gopal's allegations, he chose to tour with La Meri again in 1958.

THE TEACHING YEARS

Her second tour to South America was an artistic success, although sometimes corrupt officials made it a logistical nightmare. A famous dance critic in Montevideo asked her for the little red comb she wore in her hair. "You see, I already wear two others, this one from Argentina and this one from Pastora. So now you will join them. I have seen many Spanish dancers and I shall see many more. Yet it is long that I have worn only two combs and I think it will be long ere I wear four."

The outbreak of the Second World War ended this tour as well, and they returned to New York. Carreras and La Meri returned to NYC permanently when WWII broke out in Europe. La Meri became friends with Ted Shawn and Ruth St Denis when St Denis introduced herself and insisted that La Meri open a school of ethnic dance with her, the School of Natya. Suzanne Shelton described their alliance:

La Meri had a performing life similar to St. Denis', an early career as a movie-house dancer, a stint in a Spanish dance troupe, then years of endless tournig as a solo dancer... They were both strong personalities, both amous in their chosen field, and unlikely as it seemed, they became close friends. They met after on eof La Meri's concerts. Ruth bounded back to her dressing room and announced that they must collaborate on a center of the oriental arts. "She was a torrent of embodied enthusiasm, as easy to avoid as a urrican," La Meri said of Ruth. They discussed the idea of an artistic co-ventue and in the spring of 1940 announced the School of Natya at 66 Fifth Avenue, where Martha Graham already had her studio. Martha was on the top floor, La Meri had the one below, and Ruth moved into the ground floor studio.Since few young dancers could afford full tuition, Ms Ruth and La Meri made ends meet by holding demonstration lectures and dance programs every Tuesday evening, admission seventy-five cents. They called these Tuesday night events reunions. La Meri struck up a close friendship with another great dancer, Argentinita, who came to one of the Spanish dance reunions and returned often to teach the Natya students Coplas and the Jota. In 1944 Miss Ruth moved to California. Shortly afterwards, La Meri and ballet authority Anatole Chujoy conceived the idea of her choreographing Swan Lake using Indian dance technique. This was her first conspicuous public step away from the purely authentic in dance. It was a success, both critically and financially. Many of the classical ballet Swan Queens came to view this version of the ballet. The School moved to the upper West side when offered rent-free studio and theatre space but the audiences "which gladly packed our studios in Tenth Street simply declined to make the trek up to 113th Street." The Natya Dancers were very much in demand, but not so much for paid performances as for appearances at educational institutions. The School moved to 46th street and started making money on the Tuesday performances again. La Meri then formed a dance theatre which earned substantial money performing at the American Museum of Natural History's ethnic-dance concerts twice a month.

Meanwhile, her relationship with her husband Carreras was changing. He had many excellent qualities, but LaMeri was coming into her own as a mature artiste at the same time that it became apparent to her that he was not monogomous. "Since Australia I had been well aware that my husband was possessed of a wandering eye. Frightened and alone, I had no idea how to cope with such a state of things."

In 1944 La Meri separated from her husband. Guido had handled the finances and the business arrangements for all of her career and she tried to learn these things as best she could, but finances began a slow down-hill slide which never permanently reversed itself. The motivation for the divorce may have been Guido' numerous infidelities, but it also may have been La Meri's increasing determination to move away from traditional and authentic ethnic dance towards more creative departures which Guido was not enthusiastic about.

She then choreographed Scheherazade, which was also a success. But the need to constantly create new programs and dance works in order to hold faithful audiences began to wear on her. She became ill and temporarily closed her theater and school. When she returned to work in 1946, she started the Exotic Ballet Company, which presented the Bach-Bharata Suite, an abstract work using Hindu techniques for the interpretation of Bach compositions. This also was a success.

In 1947, she began a Young Artists series, inviting young artists of ethnic dance to appear in her theatre. The artists were offered a good stage, well lit, publicity, and fifty-percent of the gate. Fourteen young unknowns were presented, many of whom went on to highly successful careers.

THE WHEEL TURNS: THE END of an ERA

In 1948 she decided to tour Latin America as a soloist in an attempt to earn more money. She came back to NYC convinced that the era of the solo dancer was finished. The world was changing. "People wanted large companies carrying complete decor and using full orchestra. Wonder at the delicate shadings in the program of the creative soloist had worn thin...Perhaps this had been brought about by the influence of the 'colossal' screen productions, or perhaps it was simply a natural evolution. The end result was frightening to contemplate. Where in future would the dancer find the financial means to meet these new demands? " On the way home to America, she decided to expand her company, find financial aid and learn how to obtain grants.

She found her center in a financial shambles and her students convinced that she 'was sitting on a pot of money and, for some reason of my own, was refusing to help extricate us from our plight.' Most of the students decided they would be better off striking out on their own. A company of 15 quickly shrunk to three dancers. Lacking a stable company, the Young Artists Series was abandoned and performances cut down from four a week to four a month. With a company of three she could not begin her plan of large company performances. She encouraged her young dancers to pursue TV performances. "There was no more vaudeville to replenish the empty coffers of the concert artist as there had been in the days of Denishawn. Even Broadway, which so often had saved dancers of my generation financially, had shrunk from some four hundred to some forty going theatres. The rest were empty or else their marquees announced live television shows. But few of my young dancers deigned to turn to this medium, and I, the misfit, could not." For La Meri, a live audience was of the essence.

In 1949 she expanded the curriculum in her NYC dance center. "In forty-five hours of classes a week they took not only dance techniques but the study of ethnic dance, history and culture as well as choreography, music fundamentals, and costume design." However, she wasn't able to get her school approved for inclusion in the college credit system.

"Then began the years that, in slow diminuendo, saw the shrinking frame of presentation for the ethnic dancer." The Museum of Natural History's ethnic-dance series closed, despite full houses and great artists on the stage. The Joseph Mann modern dance series, a major forum for modern dance in its formative years and which had often hired La Meri to present abstract creative works based on ethnic techniques, ceased. "These two long-established and highly respected dance series had died within a year of each other. Was television luring away the audience? Were increasingly hard-to-please critics discouraging young dancers? Was a postwar America finding money too tight to spend on culture?"

In 1954 she gave up touring when she became allergic to hair dye. Since her natural color was now completely white, she could no longer perform with her male partner who was in his twenties. In 1960, "worn out by the lack of an audience for ethnic dance, frustrated by the difficulty of putting on concerts, and tired of the infighting in the ethnic dance world," La Meri left New York for Cape Cod with her sister, Lillian, who was an accomplished Spanish dancer and one of the graduates of the Ethnologic Dance Center. She intended to continue her writing and raise champion show dogs. Jacob's Pillow (Ted Shawn's school) in the Berkshires was flourishing and growing, and La Meri was often invited to teach, perform and tour with the Jacob's Pillow company. She choreographed several successful works for them that received high compliment from audiences and artists alike. From Walter Terry's biography of Ted Shawn:

La Meri, a star herself and head of the Pillow's ethnic dance department, found collaboration with Shawn rewarding and infuriating. In 1975, still busy directing, choreographing, and teaching at seventy-seven, she said, "It was twenty good years of roaring, bloody battles." She, at his insistence, choreographed for him, adapting East Indian and Spanish techniques to his style in occasional productions such as El Amor Brujo, and he put her in a retrospective ballet evocative of Denishawn, a bad piece which he said he had done especially for me [Walter Terry] because I had never seen a Denishawn performance... I have seen La Meri pacing the entire parking lot at Jacob's Pillow, her tail twitching like that of an enraged cat. I'd stop the car, lean out, and yell "What's the matter?" The answer, "That man! I could kill him!"

When her sister died in 1965 La Meri started the Ethnic Dance Arts company. Patricia Taylor wrote: "Out of nothing, she created an educated audience and a venue for ethnic dance that lasted for ten years. However, by 1980, La Meri again found herself at the end of a phase in her life. A trusted employee of Ethnic Dance Arts, Inc. had stolen a large sum of money in 1975, and the enterprise had begun to die. Her students left, retired, or had families. She realized that her dreams of creating a year-round, financially successful ethnic dance center on the Cape would never be realized."

A heart-breaker for sure! But her biography ends with the remark "I chose this road myself and chose the horse to ride it. No wooden carousel steed, he! The unpredictable, pied mustang ethnic dance has given me a wild-running, hard-bucking ride but I did catch a few brass rings."

In 1984, Hughes returned to San Antonio. She attended dance performances and maintained a busy social life and correspondence until her death in 1988 at age 89.

La Meri in Javanese Costume, photo by M Blechman

REFERENCES

Dan Knapp, Letters Reveal Legacy of Ethnic Dancer, USC News, Web. "Among the archive's contents are professional and candid photographs, news clippings and reviews, ephemera related to La Meri's performances throughout the world, and original watercolor and charcoal portraits of the dancer drawn by USC alumnus Charles James Miller, La Meri's one-time paramour and an accomplished dancer in his own right. The collection also contains more than 100 personal letters composed from the mid-1940s until her death in 1988."Dance as an Art-Form at Archive.org.

Dance Out the Answer (La Meri's autobiography) is out of print but second-hand copies are still circulating.

Divine Dancer, a Biography of Ruth St Denis by Suzanne Shelton.

Finding Aid for the Charles James Miller papers at Online Archive of California.

La Meri: A Life Dedicated to Ethnic Dance by Patricia Taylor and published in Habibi Magazine in 1997.

"Learning the Danse du Ventre" by La Meri, published in Dance Perspectives magazine in 1961.

Life and Times of La Meri, The Queen of Ethnic Dance, by Usha Venkateswaran. Extracts from a number of La Meri's letters and diaries are included. Best read after reading Dance out the Answer, since this book is somewhat disorganized and occasionally out of sequence.

National Library of Australia Trove.

New York Times obituary for La Meri.

Rhythm in the Heavens by Ram Gopal.

San Antonio Public Library Image Collection.

Ted Shawn, Father of American Dance, by Walter Terry.

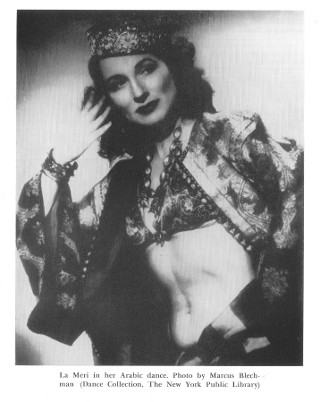

La Meri in Arabic costume. Photo: Marcus Blechman.

TIMELINE

- 1898

- Born in Louisville, KY

- 1910

- Family moves to San Antonio, TX.

- 1912

- La Meri attends a dance concert by Anna Pavlova in San Antonio, inspiring an interest in dance.

- 1914

- Father dies.

- 1915

- Attends concert of Eastern-themed dances by Ruth S Denis.

- Attends concert of Spanish dance by La Argentina.

- 1916

- Enrolls in the College of Industrial Arts in Denton, TX

- Attends concert by Ballet Russe.

- 1920

- First trip to NYC in an attempt to make her mark as a poet.

- La Meri sees Martha Graham perform a Java-ese styled dance at the Greenwich Village Follies.

- 1923

- Professional debut at the Rialto Theatre dancing prologues to silent movies.

- 1925

- Guido Carreras becomes her manager and she embarks on her first Mexican tour.

- 1927

- Her mother dies.

- 1928

- La Meri makes her debut as a solo concert dancer at the John Golden Theatre in NYC.

- La Meri embarks on a tour of South America.

- 1929

- La Mari studies the danse du ventre in Fez, Morocco, with Fatma.

- 1931

- Guido and La Meri marry.

- 1933

- La Meri publishes Dance as an Art-Form: its history and development.

La Meri in Spanish Costume, National Libary of Australia

- 1936

- La Meri arrives in Australia for her Oriental tour.

- La Meri meets Ram Gopal.

- 1940

- La Meri and Ruth St Denis found the School of the Natya in NYC.

- 1942

- School of the Natya becomes the Ethnologic Dance Center.

- La Meri gives classes and lectures for the first time at Jacob's Pillow.

- La Meri embarks on a dance tour of South America.

- La Meri gives classes and lectures for the first time at Jacob's Pillow.

- 1944

- La Meri choreographs Swan Lake using Indian dance techniques.

- La Meri and her husband separate.

- 1947

- La Meri begins a successful Young Artists series to introduce talented young ethnic dancers to the public.

- 1948

- Financial problems begin to be a serious consideration.

- La Meri publishes Spanish Dancing, considered by many to be THE definitive text on the subject.

- 1954

- La Meri gives up touring.

- 1956

- La Meri, in financial straits, retires to Cape Code with her sister and long-time creative partner, Lillian.

- 1964

- La Meri publishes Gesture Language of the Hindu Dance.

- 1965

- Sister Lillian dies.

- 1970

- La Meri establishes an Ethnic Dance Arts organization in Hyannis, MA.

- 1977

- La Meri publishes Dance Out the Answer: An Autobiography.

- La Meri publishes Total Education in Ethnic Dance.

- 1984

- La Meri returns to San Antonio.

- 1988

- La Meri dies in hospital.